1842 Orange County, VA: Four women on divergent paths

- Mar 30, 2022

- 4 min read

Updated: Mar 31, 2022

written by Zann Nelson

Part One

First was Lucy Quarles, born to freedom as a white woman in Louisa County and by 1836 had become a widow of William Quarles and owner of Bloomsbury Plantation on the Eastern edge of the Town of Orange. At her death, in 1841, she was the owner of an estimated 75 people of color. Lucy Quarles may not rate the characterization of “protagonist” in our story, yet without her decisions, the fortunes of the other three women would have been very different.

The second woman in this story was Matilda Tibbs, a woman of color approximately 40 years old and the mother of seven or eight children all owned by Lucy Quarles.

The third was Margaret; a woman of color, of undetermined age and no known surname who had given birth in 1840 to a daughter named Tabbyella; both were owned by Lucy Quarles. The 4th woman was Sukey or Susan Madison, also a woman of color believed to be about 40-45 years of old. Susan Madison and her three children Henry, Walker and Tinsley were also owned by Lucy Quarles.

Mrs. Quarles died in October of 1841. The will, probated in 1842, offered freedom to sixty six (66) of her slaves and enough funds to allow them to relocate to another state which at the time was a requirement by Virginia law.

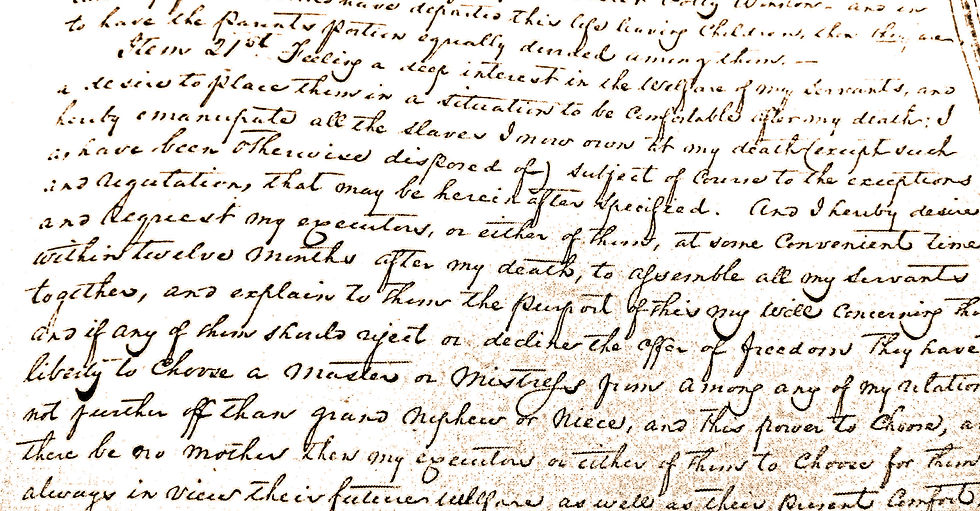

Lucy Quarles wrote in her will in Item #21, “Feeling a deep interest in the welfare of my servants and a desire to place them in a situation to be comfortable after my death; I hereby emancipate all the slaves I now own …” there were some exceptions.

We have not determined why Lucy Quarles failed to free all of her slaves, bequeathing a few to her selected relatives. Two other interesting statements in the Quarles’ will read as follows:

“If any should reject or decline the offer of freedom, they have the liberty to choose a master or mistress from any of my relations…….”

Though still a little unclear, the will implied that if not otherwise stated a mother, even one who was not emancipated, may choose or decline the offer of freedom for her children. If a child was considered to be an orphan then executors of the estate were to make the decision on their behalf

“…having always in view their (the child’s) future welfare as well as their present comfort”

These codifications and resulting choices would have a life altering impact on Margaret, Tabby Ella and Susan Madison and her children. For certain, Orange County was a tightly knit community in 1840. Lucy Quarles’ decision to manumit the vast majority of her slaves must have created quite a stir amongst slave holders and the enslaved.

The discovery of her action raises a plethora of questions: What prompted Lucy Quarles to take this course? Was anyone else doing this? Why would anyone decline or reject the opportunity to be free?

The last line # 21 is Tabyella, the baby whose mother chose chose freedom for her daughter even though they could not be together. Taby Ella was sent to Ohio with the Kenney family (also manumitted by Lucy Quarls)...note that she was 10 in 1850, born in VA but left VA as a a baby of about 2.

Part Two

The four women in our story that evolved in Orange County in 1842 were Lucy Quarles, Matilda Tibbs, Margaret, Susan Madison. Margaret was one of those who was not offered freedom. Perhaps she was in poor health and incapable of travel? The answer may yet be revealed or we may never learn the truth.

Matilda Tibbs and all of her children plus one grandchild were freed by the will and she was given ample funds for the 400 mile journey to resettlement in Ohio. Although a man by the name of Frank Tibbs was believed to be the father of the children, there was no Frank Tibbs in Lucy Quarles inventory of slaves and no one by that name was listed in the 1850 Census record for Fairfield Co. Ohio where they had relocated. Was Frank Tibbs enslaved on another plantation and not free to relocate with the family? Yet another mystery!

Though Margaret was not manumitted, she had the option to speak for her daughter. Margaret chose freedom for two year old Tabby Ella and sent her to Ohio, presumably with little chance of ever being reunited. I was able to find Tabby Ella in an 1850 Ohio Census living with a family by the Kenney who were also listed in the will of Lucy Quarles. She was listed with the surname of “Shepherd”. Hmmm? Could we find Margaret with the Shepherd surname as well? Thus far I have been able to trace Tabby Ella through 1870, before I lost the trail. No, I have not yet given up!

Susan Madison was offered freedom and declined… for herself and her children. She chose instead Peter T. Johnson, an Orange County resident and Lucy’s nephew, as their new owner.

At first blush it is perplexing to understand why anyone would decline the opportunity to be free. However, upon reflection there is some plausible rational.

If one were elderly or in poor physical health, they might not have been up to the long journey or perhaps, they had family who were owned by another and thus not sharing in that same status of freedom.

Remember that at that time the law in Virginia with only a handful of exceptions required that once emancipated the former slave was mandated to leave the state. For whatever reason one chose not to relocate, then they would remain enslaved.

Was Susan Madison elderly, infirm or was Walker Madison her “husband” and the father of her children owned by another? We do know that two other children, daughters Clara and Martha were not freed but rather bequeathed to relatives. Could Susan have made her decision based on a desire to keep the family together?

The documented actions by all four of these women generate much fodder for contemplation and shed new light on issues we may have not previously considered.

Certainly, their actions have prompted me to ask, “If I were Lucy, Matilda, Susan or Margaret, what would I have done?” Without question, stories such as these provide food for thought and insightful discussion, as we plough these fertile fields of African American heritage.